I have a normal love-hate relationship with Git, meaning I love Git when it's just me working on the project, and I hate it when I have to merge my code with someone else's. But then all marriages have their ups and downs, right. The truth is that as a coder, at some point in time, you will need Git, and once you start using it, you won't stop, even though it could get frustrating at times. So here is a cheat sheet you can use when you are revisiting Git after a long time, or want to learn more applications of Git, or if you need to time travel and get your older code back.

Warning: Git can not show you your future code; you will have to do it😜 .

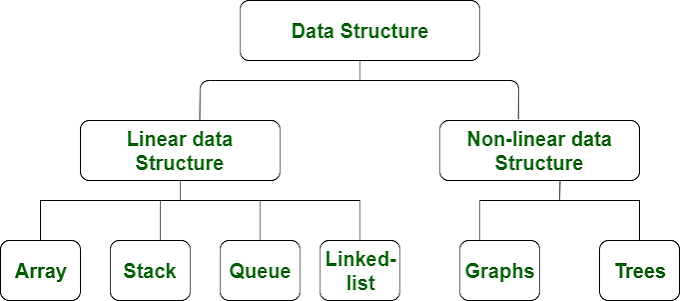

Before we dive in, let me explain the structure of Git so that you can understand the commands better.

- Repositories(repos for short): They are a collection of files of various versions of a Project.

- Remote repository: The current repo that is stored remotely/online. So the repos we see on Github or Gitlab website are the remote repos for those projects. They contain the changes made and pushed by everyone.

- Local repository: The current repo that is stored on your local device. It contains the changes made by you and can also include the changes present on the remote repo.

- Commits: They essentially represent versions of a codebase. Each commit contains changes concerning the last state of the repo.

- Branches: A branch represents an independent line of development. When we create a branch, we sort of create a brand new working directory, staging area, and project history. New commits are recorded in the history of the current branch then.

We'll learn more about these ahead, so let's start.

1) git config

Let's start with setting up our environment for Git. Run these commands on your terminal to set the configuration of Git globally(for all future repositories).

$ git config --global user.name "John Doe"

$ git config --global user.email "johndoe@email.com"Another interesting use of this command is to set up aliases. We set up an alias for the command git commit in the following command, so now git co will actually run git commit. This helps a lot with longer commands that have a lot of flags.

$ git config --global alias.co commit2) git init

Next, we need to initialize a folder as a git repository. This command actually creates a .git hidden folder inside your folder. This folder signifies that it is a git repo and stores the metadata required by Git.

//Run the following command inside the folder

$ git init//Run the following command to create a new directory that is a git repo

$ git init DIRECTORY_PATH/DIRECTORY_NAME

3) git clone

If you want to use an already existing git repo(remote repo), you need to create a copy of it on your local device first(local repo). For that, we use the clone command. First, copy the cloning link of that repo(this is usually present where the remote repo is stored).

The link will look something like this: . Once you have it, run the following command in the folder where you want this repository to be downloaded.

$ git clone LINK

$ git clone 4) git fetch

Let's say multiple people are editing the remote repository of your project, which means you all are coding collaboratively, so their changes are essential to you. To download their changes when needed, you need your local repo to know about these changes, i.e., you need to fetch the changes.

So the command git fetch downloads the remote repository details and changes on your device. Use it as follows:

//download the state for all the branches

$ git fetch //fetch for just one branch

$ git fetch <remote> <local>

//<remote> is the name of the remote branch

//<local> is the name of the local branch//an example of it is

$ git fetch origin master

5) git pull

git pull is a mix of two commands git fetch + git merge. When we used Git fetch earlier, it downloaded the current state of the remote repository first to our local device. But our files are not changed yet. To bring the changes to our file, we need git merge, which updates our local files based on the remote version.

So let's say I have a file named test.py, and on my local repository, it looks like this.

While the remote version of the file is as follows

$ git status //a sample output of this command is as follows

On branch master

Your branch is ahead of 'origin/master' by 1 commit.

(use "git push" to publish your local commits)

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

README.txt

lab1The suggested commands above are all covered in this blog, so jump to any of them for better understanding.

7) git add

The next step for us is to tell Git about the changes that we want it to remember. So for each commit, we use the command git add to add changes to the folder that we want to reflect in that commit.

So let's say I declared a new variable in a file called test.py in my git repo named GitTutorial. I want to inform Git about this change and get it to save this change. Then I will use the Git add command as follows:

$ git add /path-to-test-py/test.pyNow when you run the git status command, you will see this file name is written in green because Git is up to date with this file.

If you need to delete a file or folder, you can check out the git rm command.

8) git commit

Now that we have added or deleted the changes we need to inform Git about, we commit the changes. This, in a way, finalized the next version of our codebase. We can go back to all the past commits to see the version history. The command works as follows.

$ git commit -m "The message you want to write to describe this commit"The -m flag helps write a message that describes the commit.

9) git push

Till now, whatever we were doing was happening to our local repository, but at some point, we needed to push it to the remote repository as well so that others could see and use our code. The git push command does this. Call it as follows:

$ git push <remote> <local>

//<remote> is the name of the remote branch

//<local> is the name of the local branch//an example of it is

$ git push origin master

The above command pushes our local commits to the master branch.

10) git log

Of course, after performing multiple commits, we will actually want to look at how the code has evolved. As we will learn ahead, there are also chances that many people make commits to their branch and at some point might want to merge their branch with a different branch. All such actions that have been done in our repo can be accessed using the git log command like so:

$ git log --graph --oneline --decorate

//a sample output

* 0e25143 (HEAD, main) Merge branch 'feature'

|\

| * 16b36c6 Fix a bug in the new feature

| * 23ad9ad Start a new feature

* | ad8621a Fix a critical security issue

|/

* 400e4b7 Fix typos in the documentation

* 160e224 Add the initial code baseHere, the alphanumeric codes we see at the start of each line represent each commit and will be used if we want to revert or perform other functions.

Also, see git shortlog.

11) git revert

We come to the part of Git that we will need when we make mistakes and want to time travel to the previous code. git revert can be described as the undo button, but a smart one. It doesn't just go back in time but brings the past changes into the next commit so that the unwanted changes are still a part of the version history.

For git revert, we will need the commit codes that we saw earlier in the log.

$ git log --oneline

86bb32e prepend content to demo file

3602d88 add new content to demo file

299b15f initial commit$ git reset --hard c14809fa

//this command will not changes files that you have not git added

There are many other ways to revert, so do check those out once, in case you need them.

12) git branch

This command lets us create, list, rename, and delete branches. Let's look at a few examples.

//this lists the name of the branches present

$ git branch

main

another_branch

feature_inprogress_branch//delete a branch safely

$ git branch -d <branch>

$ git branch -d another_branch

13) git checkout

The git checkout command lets you navigate between the branches created by git branch.

//switch to a different branch

$ git checkout <branch_name>

$ git checkout another_branch//create a new branch

$ git checkout -b <new_branch_name>

$ git checkout -b new_feature_branch

14) git diff

There are times when we will need to compare the code between versions or between branches; that is when we use git diff.

//print any uncommitted changes since the last commit.

$ git diff//compare code between two branches

$ git diff branch1 branch2//print the uncommitted changes made in one file

$ git diff /filepath/filename

15) git rebase

Coming to our final command, the one I sort of dread the most :P. There will be times that we need to merge codes or pull code from master to our branch or many other situations.

To tell you in a gist: